Three and a half years have passed and it's still hard to process.

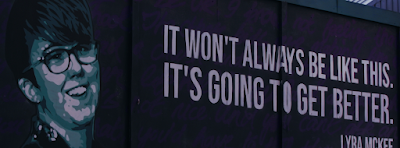

Lyra McKee was a journalist who had remarkable drive and plenty of ability.

A Forbes "30 Under 30" honouree, she didn't follow normal career patterns.

She did things her way and simply focused on becoming a great investgative journalist.

The Belfast woman had an exciting career ahead of her, having embarked on a two book deal with Faber and Faber.

But all that was extinguished when she was cut down in 2019 by a dissident republican bullet during a riot in the Creggan area of Derry.

Lyra died doing the job she loved.

But what made it hard to take was that she hadn't even reached her peak.

Those of us whose paths crossed with Lyra during her career discovered she was smart, funny and curious.

She was also challenging, driven, entrepreneurial, progressive, accomplished, loyal and brave.

Even though I would never claim to have known her well, the first time I came across her was while working as the Director of Media and Corporate Relations at the University of Ulster.

She had heard from a mutual acquaintance that I had previously worked as the Ireland Political Editor for the UK and Irish national news agency, the Press Association and was keen to understand how it operated.

We met in a Belfast city centre coffee house and spent an hour and half chatting about her unconventional career, my much more conventional one, about how the Press Association worked, about her passion for investigative reporting and about film criticism.

It was a fascinating and fun encounter and her enthusiasm for her profession was striking.

We kept in touch, mostly through social media as I followed her career with interest.

Our last interaction was about two weeks before her death as I waited for a delayed Easyjet flight in London's Stansted Airport.

Lyra, who loved her 'Harry Potter' and Marvel movies, was looking for a recommendation for a Netflix series to watch.

I pointed her in the direction of 'Russian Doll' and she immediately fired back it looked good and she would check it out.

To this day, I still don't know if she ever managed to watch it.

But it was a typical exchange - brief, good humoured and to the point.

Lyra was complimentary about this blog which she didn't have to say nice things about but that was the type of person she was.

While she loved Marvel and Harry Potter films, her big passion was investigative journalism - a fact rammed home in her friend Alison Millar's superb documentary 'Lyra'.

The feature length documentary is compiled from archive footage assembled by Millar of Lyra on cameras and phones and from recollections from family, friends and acquaintances.

We see her at the start of the film, fluffing her lines as she appeals for financial support for an online journalism venture.

And while Millar grimly pieces together the terrible events leading to her death, she also compellingly and humourously tells the story of how Lyra became the irrepressible force she was.

Executive produced by Hillary and Chelsea Clinton, the film notes Lyra was "a ceasefire baby" - a young person born at the tail end of the Troubles in 1990 and raised in the wake of the 1994 IRA and loyalist ceasefires.

Raised in the Ardoyne area of North Belfast, she was part of a generation who were dangled the promise in the Good Friday Agreement of peace, prosperity and real opportunity.

But that isn't how it turned out for many of her contemporaries in working class nationalist and republican communities or over the peace walls in loyalist neighbourhoods.

The society Lyra grew up in remained broken and divided, with a lot of young people either trying to find an escape from the deprivation around them through addiction, through crime or by taking their own lives.

Suicide rates rocketed in Northern Ireland after the Troubles while they didn't in England, Wales and Scotland.

Lyra noticed it and wrote about it as a 16 year old, winning a Sky News Young Journalist competition.

This was a seminal moment in her career - although Millar's film tips its hat to Lyra's granny who encouraged her to be a writer.

While she dabbled initially in poetry, it was investigative journalism that ultimately captured her imagination.

And as she pursued her dreams, Lyra defied convention.

A gay Belfast woman from a working class Catholic/nationalist neighbourhood that bore the scars of conflict, she forged her own career path instead of slavishly following the model the rest of us in the profession pursued.

Lyra was a young woman in a hurry. There were loads of stories she wanted to tell, loads of people and causes she wanted to champion, loads of buried secrets she wanted to unearth.

She wasn't going to let the traditional model of journalism and its insistence that she had to serve her time stand in her way.

At one point in the documentary, she quotes someone telling her: "The brick walls aren't there to keep you out.

"They're there to see how badly you want it."

And as the film demonstrates, she really wanted to be an investigative journalist badly, which is why she worked for new digital journalism channels like Mediagazer, Mosaic and BuzzFeed News.

It took me a while to really appreciate Lyra's entrepreneurial approach to our profession and I'm sure I wasn't alone.

Most of us followed the traditional route of serving your apprenticeship in newspapers because it provided a blanket of relative financial security.

Lyra just had an entrepreneur's mindset, a "Go Do" attitude and threw herself into emerging online news ventures without worrying about the financial consequences.

In 'Lyra,' we hear her observe that thinking about money can constrain your creativity - although she adds rather impishly that sometimes you get lucky and people pay you for the thing you love.

During the film, we see how she achieved just that and hear directly from those who were just mesmerised by her passion for telling difficult but important stories when they encountered her as a journalist.

Janet Donnelly, whose father Joseph Murray was shot during the Ballymurphy massacre in West Belfast in 1971 where British Paratroopers killed 10 innocent civilians, humourously recalls Lyra's jaw dropping as she opened up her extensive archive on the case to her.

A bond was forged to the point where Janet informed her about her father's body being exhumed to recover a bullet lodged in his skeleton.

Fr Martin Magill admits to being deeply impressed when she approached him for help while writing 'The Lost Boys' - a book she never got to complete.

Lyra was investigating the disappearance of Thomas Spence and John Rodgers, two boys aged 11 and 13 who vanished at a bus stop in West Belfast in 1974 on their way to school and the mysterious disappearance of several other children during the Troubles.

The priest would later preach at her extraordinary funeral in Belfast's St Anne's Cathedral which was attended by the British and Irish Prime Ministers, the Irish President, Westminster and Stormont leaders and he used the occasion to issue a heartfelt plea to make politics in Northern Ireland work.

During her shortlived career, Lyra tackled issues that even the most seasoned hack would have found challenging.

She did so with passion and compassion.

Millar's film is arguably at its most powerful, though, in its most intimate sequences whether its the scenes of members of Lyra's family preparing to pick up a posthumous award at an event in London or her partner Sara Canning musing how she could be walking past her killer any time on the streets of Derry

Sara raises a smile as she recalls Lyra's inability to keep a secret that she had purchased a ring which she intended to propose to her with in New York.

There's a touching sequence where her sister Nichola Corner goes through Lyra's belongings, treasuring the moleskin notebooks she used to write in and her dictaphone which is all the more precious because it contains recordings of her voice.

A nephew three years younger than Lyra, Andrew recalls coming out as gay to her and being relieved to hear that she was wrestling with the same issue.

Coming out is never easy but especially at that time in Northern Ireland where Evangelical Protestant preachers and Catholic priests denounced their sexuality.

In a nice touch, we see Andrew pat a mural painted in her honour near Belfast's Sunflower Bar as he walks past it on the street.

An encounter with Muslims in a Florida mosque while on an exchange trip to the US would have a profound impact on Lyra and it formed the basis of her celebrated TedX Stormont talk which pleaded for tolerance and emotionally intelligent conversations about homophobia from people on both sides of the debate.

Some of the hardest scenes in 'Lyra,' though, are those that show the raw heartache of her mother Joan, who died shortly before the first anniversary of her daughter's killing and also the family - especially as dissident republicans are arrested for their part in the killing.

Standing amid dissident republican protesters outside Bishop Street Courthouse in Derry, Millar takes a leaf out of Lyra's book and engages them directly in conversation.

Insisting the man who is being charged is innocent, the protesters shuffle awkwardly when challenged by the filmmaker that surely the best way to demonstrate that is by helping identify the gunman?

As Lyra observes in the film: "Northern Ireland is a beautiful tragedy strangled by the chains of its past and its present."

The court protest simply underscores that fact.

As the dissident republican omerta around her death demonstrates, Northern Ireland is still a society whose different factions are struggling to acknowledge uncomfortable truths about what they did.

People are still finding it hard to reconcile competing narratives.

Sometimes, though, you need someone to just bust through the conventions, puncture those awkward silences and challenge the competing narratives if a divided society is to progress

With its heartbreaking score by David Holmes, Millar's film shows Lyra did just that and did it for all the right reasons.

The question is: three and a half years on, who will pick up her baton?

('Lyra' opened in UK and Irish cinemas, including the Queen's Film Theatre in Belfast, on November 4, 2022)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment